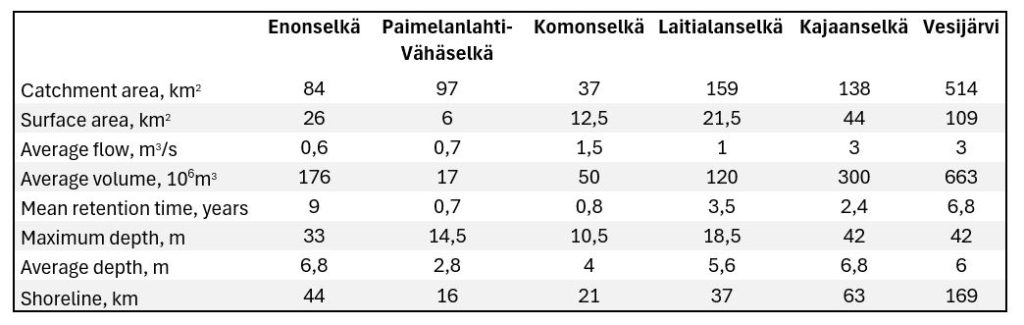

Hydrological data for open water areas in Vesijärvi and the lake as whole.

Lake Vesijärvi story

These days Lake Vesijärvi provides many recreational uses. When the weather is nice, people head for the harbour, a popular ‘living room’ for the people of Lahti. It’s hard to imagine that the area around Sibelius Hall used to be bustling with industrial activity and that Lake Vesijärvi was in the poorest state of Finland’s large lakes. Today’s situation has been achieved through restoration and cooperation. And the work is still ongoing.

Industrialisation and urban growth led to serious eutrophication

Lake Vesijärvi – created after the Ice Age some 10,600 years ago between the Salpausselkä ridges – is the oldest of Finland’s large lakes. It is affected by the groundwater and naturally very clear, with plenty of fish and rich in the variety of species. Lake Vesijärvi is a low-humic lake, but it is not naturally as oligotrophic as other Finnish lakes of the same type. In the old days Lake Vesijärvi was particularly well known for its large bream.

The lake’s surface level was lowered several times between the 17th and 19th centuries by a total of more than three metres. Agriculture began in the 17th century in the area, and intensified in the 20th century. In the late 19th century, Lahti became a transport hub after the completion of the canal (1870–71) and the railway line (1869), with sawmill and forest products industry springing up after this.

The population of Lahti increased sharply, particularly after the Second World War. The wastewater management capacity could not keep up with the population growth, and poorly cleaned wastewater was allowed to run into Lake Vesijärvi for decades. In addition to this, groundwater was sourced around the lake, reducing the volume of good-quality groundwater entering the lake.

The first signs of eutrophication in the southern parts of Lake Vesijärvi were detected already in the early part of the 20th century. In the 1920s it was first discovered that blue-green algae is a toxin to warm-blooded animals as cattle died after drinking water containing it. Eutrophication accelerated from the 1920s to ‘60s, spreading all the way to the northernmost basin, Kajaanselkä. In the mid-1960s, the water was green in all parts of the lake. The pH in the surface water was high and the deep basins largely anoxic. Since the 1960s, Lake Vesijärvi was in the poorest condition of all the large lakes in Finland.

Something had to be done / The idea of restoring the lake arises

In 1971, Finland’s first municipal environmental protection committee was established in Lahti. The committee drew up the city’s environmental protection programme, at the heart of which was the protection of Lake Vesijärvi. Upon the committee’s recommendation, Finland’s first municipal limnologist’s position was established in Lahti in 1975.

In the early 1980s, Lahti decided to change environmental problems into an opportunity. The city’s environmental department realised that the management of environmental problems engenders research, as a result of which environmental expertise will grow. Many political decision-makers also embraced environmental issues. Funding was obtained for the protection of and research into Lake Vesijärvi, which also enabled the Vesijärvi project to get started in 1987. Investments by the city increased environmental awareness and increased the number of decision-makers that took environmental matters seriously.

Lake Vesijärvi project – pioneering lake restoration

When a new, modern sewage treatment plant was completed in 1976, no more wastewater entered Lake Vesijärvi. The water quality of the Enonselkä basin recovered well, with phosphorus concentrations reducing to less than a third of the highest level. Nevertheless, there was still plenty of blue-green algae in the 1980s, resulting in fishkills, among other problems. The professional fishermen of Lake Vesijärvi lost their livelihood and recreational fishing ended almost completely. The common phrase was that “even pebbles float in Lake Vesijärvi” as the summer sun hardened what could be a layer of up to ten centimetres of blue-green algae on the surface.

The cause for the blue-green algae problems was suspected to be a distorted fish population, which resulted in management fishing experiments and extensive preparation to cooperate with research organisations, universities, authorities, fishermen and the locals. Between 1987 and 1994, the Lake Vesijärvi project focused on reducing the negative impact of blue-green algae and restoring conditions enabling recreational use.

The restoration measures were based on research findings. Research by the University of Helsinki confirmed that roach contributed to an internal load in the lake, and as a result a massive food web restoration was started. Intensive fishing focused initially on the southern parts of the lake with the removal of over a million kilograms of fish (approx. 500 kg per hectare) between 1989 and 1993, amounting to three quarters of the roach and smelt population. Nothing like this had been done previously in Finland, nor indeed anywhere else in the world in a lake of this size. At this point, pike-perch was introduced to boost the effects of the intensive fishing.

The food web restoration was effective and the blue-green algae disappeared. In the mid-1990s, the water quality and food web structure was very good. As the water became clearer, submerged plants extended to the depth of up to four metres, which helped to keep the water clear. As the lake was healthier, interest for the shoreline and building on it increased. The Sibelius Hall and new residential areas sprung up in what used to be an industrial area.

Continued restoration

At the turn of the millennium, the lake’s condition began to deteriorate again, resulting in a new Vesijärvi project from 2002 to 2007. This was an extensive project that intensified management fishing, monitored status and load, and managed external load, rural wastewaters and stormwater.

In the early 2000s, a message was received in Lahti from the government’s environmental administration that no significant additional funding was forthcoming after the second Vesijärvi project, despite the fact that the lake’s condition was again deteriorating. It was established that the lake requires continuous management and could not be left to rely on short-term and uncertain project funding. As a result of careful discussions involving a number of parties, the decision was made to establish the Lake Vesijärvi Foundation.

Thanks to the Foundation, better financial resources have enabled management measures to continue, in addition to extensive research and monitoring being carried out. The structure of the fish fauna has been supported by continuing intensive management fishing and stocking pike-perch to control the smelt population.

High levels of blue-green algae in the southern parts of Lake Vesijärvi were tackled with long-term and extensive oxygenation that was started in the winter of 2007–2008. The effects of the oxygenation experiment that was eventually discontinued in 2019 were followed closely. The experiment increased the oxygen situation in the deep basins considerably and improved the living conditions of the zoobenthos, but the effects were limited to small areas.

Controlling non-point pollution is very difficult and so far there are insufficient methods to deal with it comprehensively. Work to control external load by agriculture and forestry on Lake Vesijärvi has been carried out by building a considerable number of various water protection structures together with the landowners. The condition and operation of the structures has been monitored and the structures have been maintained. Wastewater from rural areas and stormwater from urban areas have been adjusted. The single most important measure has been to channel stormwater from the Lahti city centre to Hennala, away from Lake Vesijärvi.

Getting better

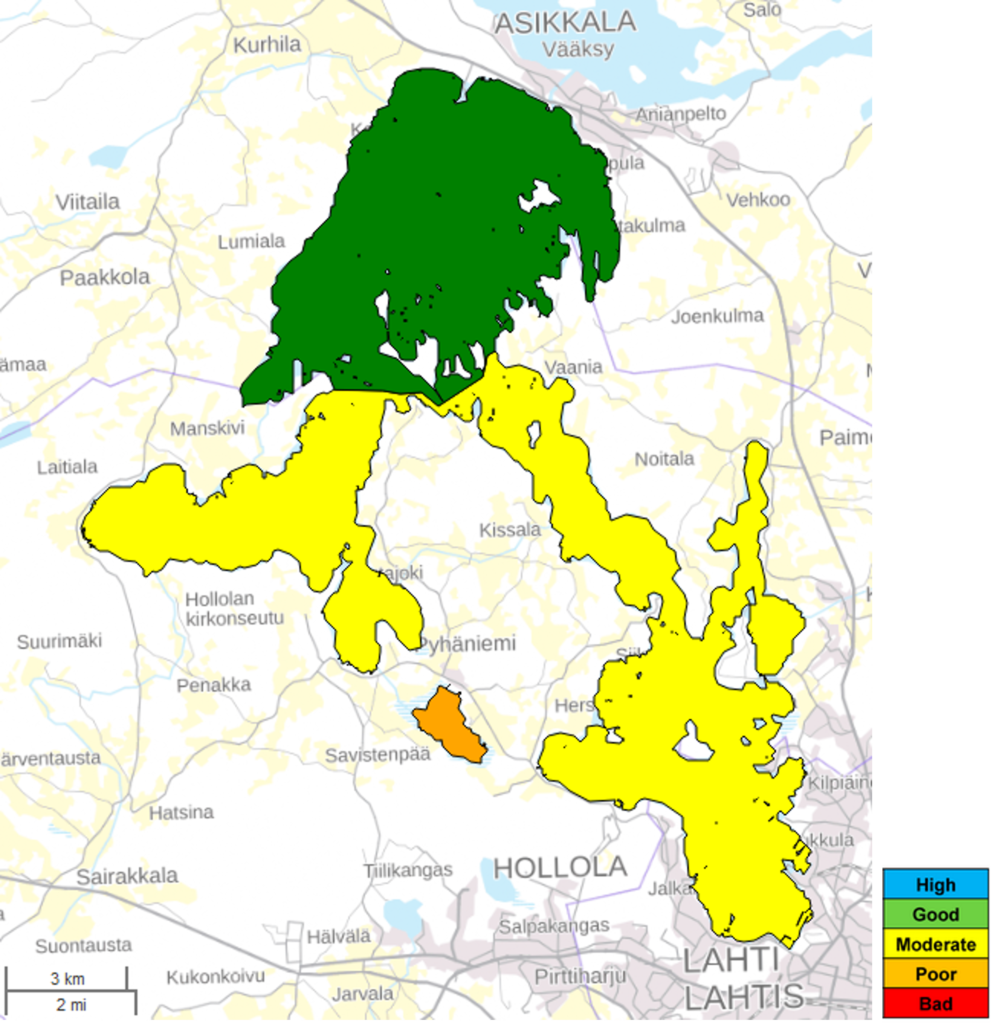

According to the latest classification, carried out in 2019, the northern part of Lake Vesijärvi is in good ecological status (Kajaanselkä basin), and the rest of the lake is in moderate status. However, there are some promising indications. In recent years, phosphorus concentrations indicating good ecological status have been measured for the first time in the Enonselkä basin, but the chlorophyll concentration has not yet fallen to a similar extent. The fish population in central areas of the lake is normalising and the zooplankton is also developing favourably. Thanks to long-standing fisheries management, the lake is currently considered a “good fishing lake”.

Climate change poses a challenge if increased precipitation adds to the load from the drainage area and high summer temperatures affect the fish and contribute to more blue-green algae. Increasingly windy weather conditions may increase sediment to be mixed with the water.

There is still a huge phosphorus deposit in the sediment, especially in the southern parts of Lake Vesijärvi. In terms of the phosphorus concentrations of the surface waters, the shallow areas are major sources of internal load. In addition, the phosphorus released from sediments in the deep areas are also important in the end of the stratification period. It is encouraging that these days more phosphorus is buried in the sediment than is released. However, one of the key questions in the coming years is whether we should remove phosphorus from the lake or bind more of it to the sediment. The removal of phosphorus from the hypolimnion is currently being investigated.

The improvement of Lake Vesijärvi calls for extensive research. We also need a broad social debate and courage to make decisions, but also resources. Lake Vesijärvi’s committed research community plays a key role in the identification of the current status, its development, and when choosing measures.

Current status of Lake Vesijärvi

As defined by the criteria of the European Water Framework Directive, the current ecological status of Lake Vesijärvi is largely moderate. The northernmost part of the lake, Kajaanselkä basin, is now in good status (Figure). The evaluation is done every six years, most recently in 2019.

The water quality varies in the different basins of Lake Vesijärvi. Vähäselkä and Paimelanlahti are the most eutrophic basins. Enonselkä and Komonselkä are also euthophic, while Laitialanselkä and Kajaanselkä are in better condition.

Of the large lakes in Finland, Lake Vesijärvi was in the worst condition in 1970s and 1980s. The status has improved greatly thanks to active management and restoration, which is still ongoing to reach good ecological status.

The ecological status category shows the extent that human activity has changed the state of the water body from its natural state. There are five categories: high, good, moderate, poor and bad. The goal is to ensure that the ecological status of lakes is good or high.